Speaking Data to Anecdote: The Reality of Representation in the U.S. Art World

Sharing the Burns Halperin report

Hi Everyone,

Thanks so much again for subscribing and for those of you celebrating, wishing you a relaxing holiday season.

I’m devoting this week’s newsletter to the Burns Halperin Report, which some of you may have heard of already. (You also might note—if you’ve listened to it by now—Helen Molesworth covered it in Death of an Artist’s last episode.) Why this focus? This newsletter aims to highlight the best art content out there. And I feel the report is some of the best recent contemporary art journalism. The report presents crucial information to the art community. It speaks truth to power—or more specifically, data to anedcote. And it evinces time, care, and thoughtfulness, which (as I have said previously) I find lacking in most current art writing.

If you don’t know about the report, in brief, it’s in its third edition and it aims to figure out, through quantitative work, if U.S. art institutions and the art market are diversifying as much as they say they are. While I encourage everyone to read the full 2022 report, I wanted to share its conclusions below.

Overall, the report finds that the “art world likes to think of itself as a bastion of progressive values…[yet the] data shows that its perception of progress far outpaces reality.” Burns and Halperin found that “a few high-profile exhibitions and auction results obscured a far more entrenched system of racism and sexism that was not changing anywhere near as quickly as the triumphant headlines suggested. In fact, it was barely changing at all.”

The report examined representation in U.S. museums and the art market for work by Black American artists, female-identifying artists, and Black American female-identifying artists. They analyzed museum acquisitions (nearly 350,000 objects) and exhibitions (almost 6,000) plus auction results from over more than a decade. They received leading galleries’ data on representation and sales. They surveyed 31 institutions, ranging in size and budget from The Met to the Phoenix Art Museum. The report also acknowledged that “applying a concrete definition to something as mutable and complex as identity is a flawed exercise.” However, their hope is that even such imperfect data can “serve to challenge assumptions about how quickly progress is made, explore where progressive change is happening, and push museums to better reflect the world we live in.”

The major conclusions of the report are below. (And please note I am quoting their conclusions verbatim to ensure clarity):

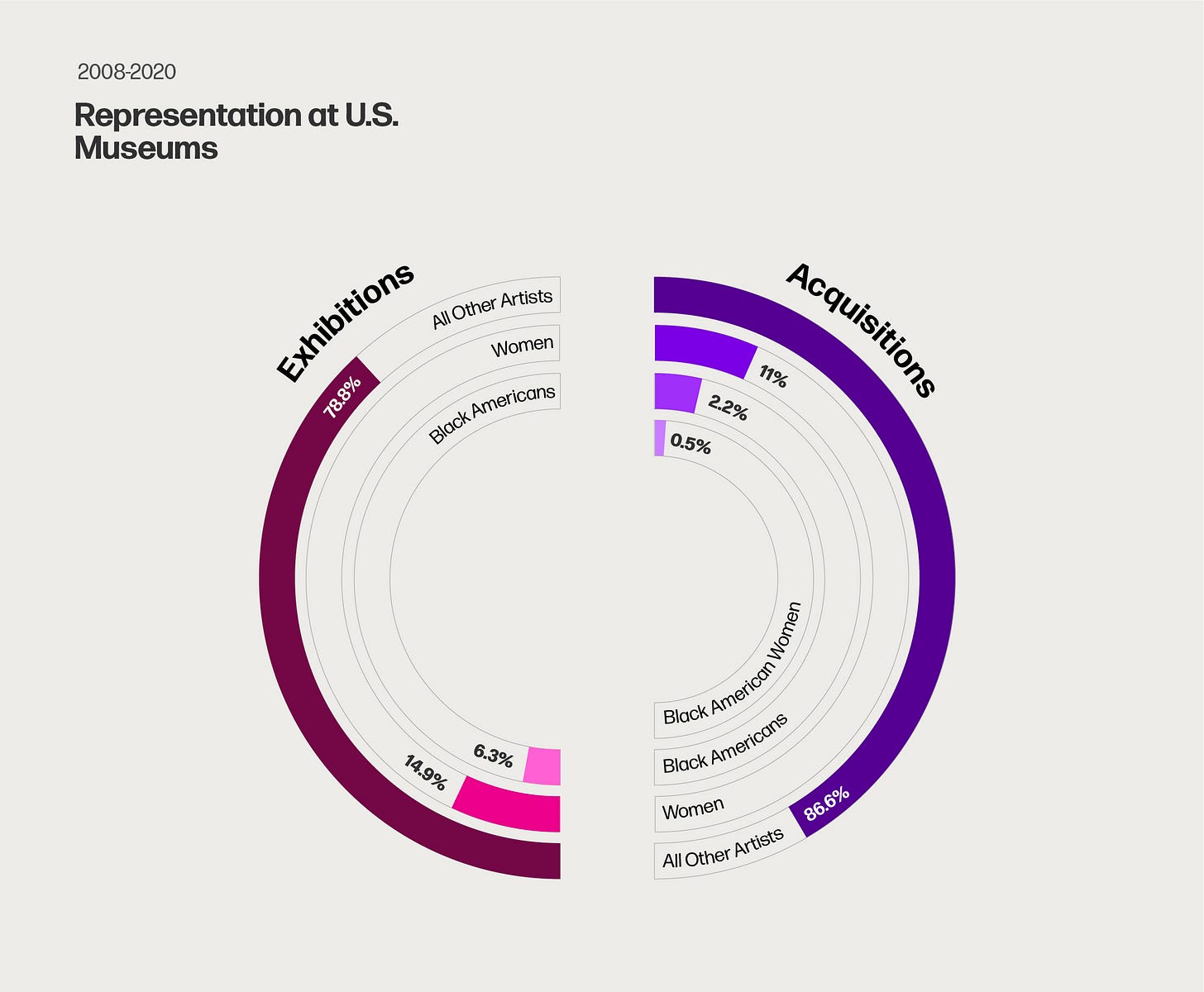

Between 2008 and 2020, just 11 percent of acquisitions at U.S. museums were of work by female-identifying artists and only 2.2 percent were by Black American artists. These totals are around a fifth of what they would be if museum collections actually represented the current population of the United States.

Where racism and sexism intersect, the situation is particularly extreme. Just 0.5 percent of acquisitions were of work by Black American women, even though they comprise 6.6 percent of the U.S. population, meaning they are underrepresented by a factor of 13.

The art market is not much better, although it has shifted more profoundly in recent years. Art by women accounts for 3.3 percent of global auction sales between 2008 and mid-2022 ($6.2 billion of the total $187 billion spend); art by Black American artists represents 1.9 percent ($3.6 billion); and Black American female artists comprises just 0.1 percent ($204.3 million).

All three markets recorded their highest totals ever in 2021. Adjusting for inflation, the overall fine-art auction market grew around 30 percent between 2008 and 2021, while the market for work by female artists grew almost 175 percent, the market for work by Black American artists grew almost 400 percent, and the market for work by Black American female artists grew more than 700 percent. These figures sound impressive: but in reality, these markets cumulatively represent $1.5 billion of the $15.9 billion spent on art at auction that year.

The data also reveals the (sometimes short-lived) impact of broader social movements. Although acquisitions of work by women peaked in 2009—13 years ago—the next two most consequential years came in the wake of the #MeToo movement in 2016 and 2017.

Acquisitions for work by Black American artists peaked in 2015, two years after the founding of the Black Lives Matter movement. The best year for museum acquisitions of work by Black American women came after the start of both campaigns, in 2018.

Again, while I encourage you to click in and read the full report, the major takeaway is this: the art world is saying it is diversifying but when you look at the data, it is, in the words of Burns and Halperin, “failing to meet the moment.”

Burns and Halperin are importantly not stopping with this report. They want to turn their project into an annual effort and a searchable database. They’ve also started to publish a series of articles focused on encouraging change. Naomi Beckwith has written on timelines for collection change. Mia Locks has written on how to make change in the museum workplace. And I am sure there will be more impressive contributions released in the coming weeks and months. I would also expect (and hope) to see more organizations funding this work. (UBS, Sadie Coles HQ, Anthony Meier all provided funding. Lobus; SMU DataArts, Museums Moving Forward, and the Black Trustee Alliance are all mentioned as partners.)

Thank you, Charlotte Burns and Julia Halperin for doing this important work and I hope this newsletter helps to further spread the word about it.

Wishing everyone a good rest of 2022.

Best,

Matthew