How Should the Art World Respond to the Climate Crisis?

Hello Everyone,

Hoping you’re well.

I’m shifting the format this week to focus on one article and respond to it. The article is a recent opinion piece in ArtReview, “Eco Exhibitions Won’t Save Us,” written by the magazine’s Managing Editor, Marv Recinto.

For those of you who have been engaged with political and socially-engaged art, Recinto’s opinion is nothing new. She uses the ongoing Hayward Gallery exhibition, “Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis,” and other recent “ecocritical” shows in London to say that while they have the “potential to inform ideological narratives surrounding the ecological crisis, they can so often feel futile in the face of real environmental devastation.” In the face of this futility, Recinto’s belief is that artists and institutions need to take action.

She explains:

“What I’d like to encourage, then, is ecological art’s concerted shift towards praxis. The public often laments, as in one recent reader’s letter to The Guardian, a sense of hopelessness that ‘climate activism is doomed to fail…in the face of corporate greed, government inaction and rampant consumerism’. Which is why ecological artists and exhibitions should perhaps turn to an ecological artistic praxis.”

Recinto then cites Documenta 15 and its inclusion of “many interdisciplinary works of this type,” such as those by INLAND, and Marwa Arsanios.

She then ends with the following:

This proposed shift in art’s function from the production of speculative art objects to one of material praxis, particularly with regard to ecological art, inevitably dredges up the age-old question: what is art’s function? Given the current state of ecological degradation, perhaps it’s time for a more concerted effort towards action. There are certainly limitations to this approach, particularly within the gallery space, which can’t house sheep to be shepherded, but perhaps it’s more a question of a shift in emphasis, towards practices that combine art and activism and actively engage the viewer. Does this necessitate a fundamental shift in how we define art? Yes. But in times like this such rules are made to be broken.

I greatly appreciated reading Recinto’s call to action and it’s been good to see the article being shared and commented upon. And I am sharing it here to continue to spread her perspective. However, I’d like to also add something to her call for action, based on my study of past political and social movements in the art world, particularly my first book, Kill for Peace: Art Against the Vietnam War (2013).

In brief, while emphasizing actions is important—and I think actions by artists are crucial at this moment—there is risk in dismissing the efficacy of other types of artistic work that seek to protest environmental degradation.

I say this because while actions/praxis might seem to provide the most immediate and direct effect, history has shown us, with regard to political- and socially-engaged art, that to have “maximum” effect, one needs to be sensitive to how much an audience will open to receiving a message and then acting upon it.

For example, a small collector audience (potentially more able to make substantial political or corporate change than a much larger group, due to personal and professional networks) might dismiss a street protest or activist organization out of hand—as too direct, unartistic, uncreative, etc. Yet they could be very open to considering an artwork on the same topic in an art gallery, which could then percolate in their minds and potentially result in their engagement with the issue. Think, for example, the way in which ACT UP and Felix Gonzalez-Torres activated their audiences in dramatically different ways during the AIDS crisis—and Gonzalez-Torres’ comment that “the most successful of all political moves are ones that don't appear to be 'political.’” The difficulty here is the less perceivable effect, but this lack of data shouldn’t discount efficacy.

Recinto’s article also speaks to a frustration artists have in times of crisis: to quickly understand the range of “effective” options available to them and inherently the art history of protest. My effort to solve this problem, as part of my work on Kill for Peace, was to propose a typology of antiwar artistic engagement—which I think can be easily transferred to engagement with the climate crisis or other political issues. Some of these types are action-oriented while others less so.

I am dedicating the rest of this newsletter to resharing some of these options. I also want to encourage others to continue to share this history of protest (especially with younger generations, who might not know much about them) because one of the main problems with political art is its history gets forgotten when times are better—and ruling powers survive due to this discontinuity. Or, as Giovanni Arrighi argued,

One continuing sociological characteristic of these rebellions of the oppressed has been their “spontaneous,” short-term character. They have come and they have gone, having such effect as they did. When the next such rebellion came, it normally had little explicit relationship with the previous one. Indeed this has been one of the great strengths of the world’s ruling strata throughout history—the non-continuity of rebellion.

Below are the major types of antiwar art I classified in Kill for Peace, which again, I hope can be seen as easily transferrable to artist’s stances on the climate crisis and be used by those looking for ways to engage. (I’ve also included a few representative works to illustrate the types. And there are other types but I am trying to distill the most influential here.) The types mentioned below were more abundant and influential at different times of the war, and can only best be understood by knowing the historical context (the events of the war), which you can get a better sense of by reading the book, which explains the conflict and artistic engagement in chronological order.

Extra-Aesthetic Actions

The term extra-aesthetic action means to refer to marches, advertisements, strikes, walk-outs, and petitions, which lacked a visual aspect and did not in any way relate to what could be considered an art context. Extra-aesthetic action involved more artists than any other over the course of the Vietnam War.

Direct Evidence

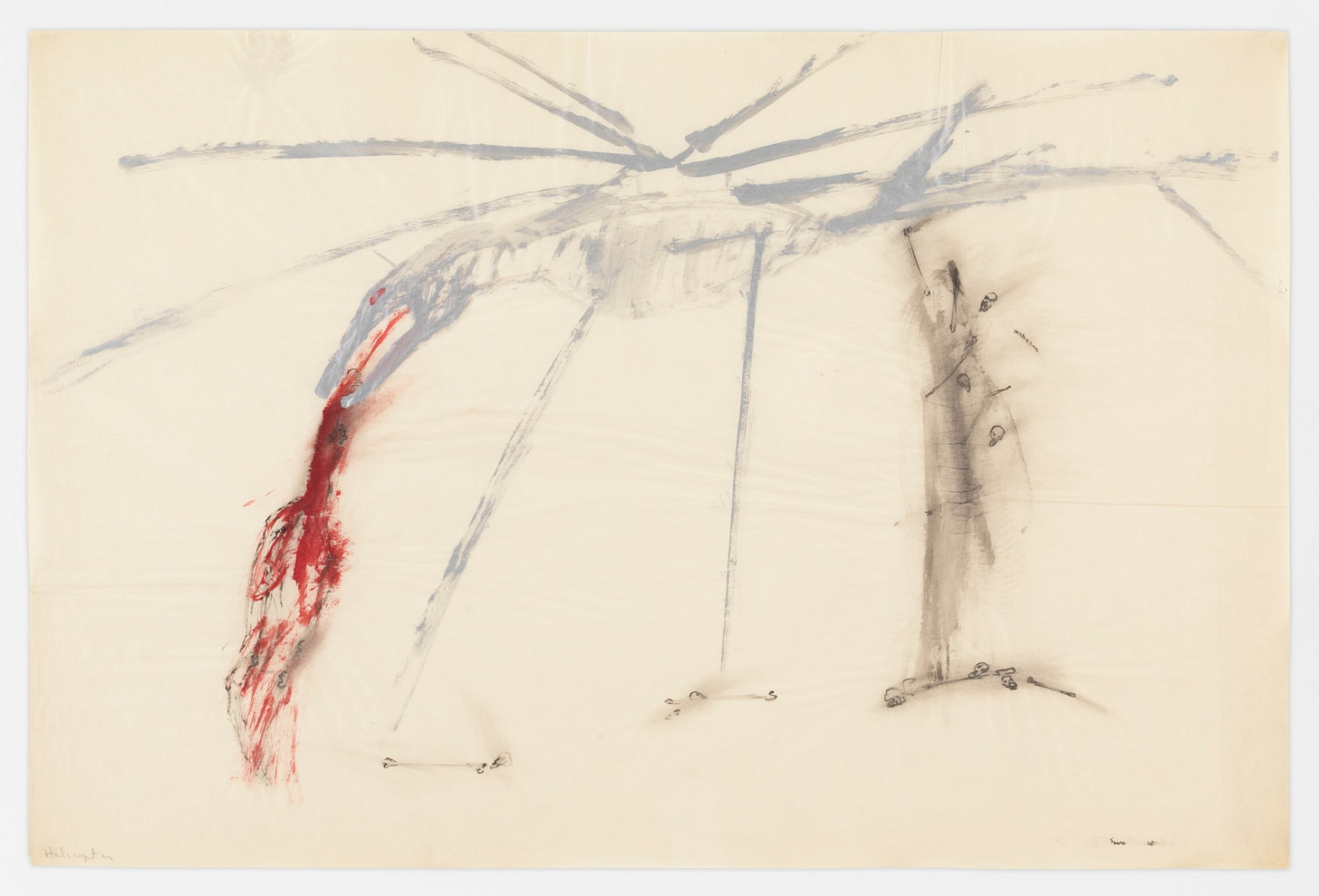

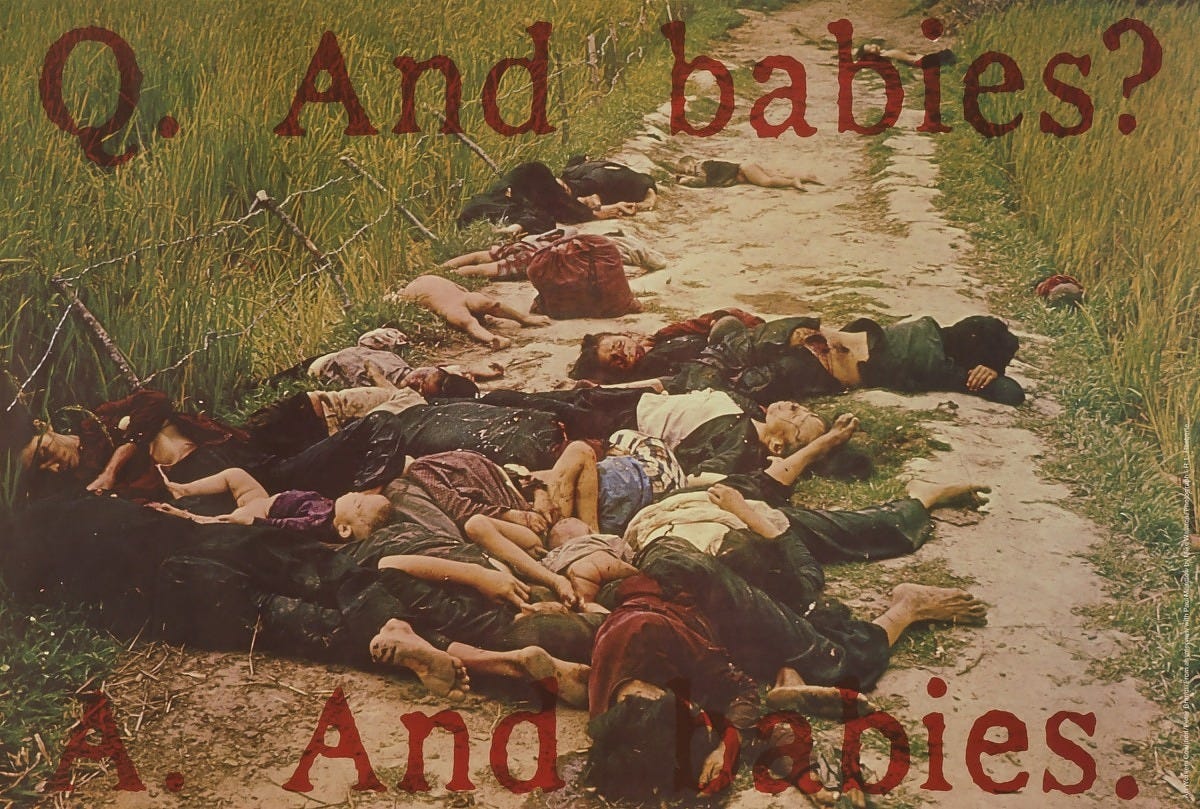

Direct evidence as a legal term refers to evidence directly related to the facts in dispute. In terms of the war, this term was used—as curator Maurice Berger did in his landmark 1988 exhibition of antiwar work, “Representing Vietnam”—to identify photography from the war front that characteristically featured Vietnamese women and children civilians injured by American attacks. Since the dawn of photography, images of direct evidence from the war front have been central to dissent and it was no different during Vietnam. From 1967 they became one of the dominant ways through which artists protested the war in their work. These works could take a variety of forms: collages, films, paintings, and even performances. Works incorporated single images or combinations of images from the war front, and the formal strategies used to incorporate these works were particularly dynamic.

Defacement

Over the course of the Vietnam War, a host of works took patriotic symbols and visually reversed what they stood for, so that rather than stand for symbols of freedom, idealism, and democracy, they were subtly and not-so-subtly revised into images representative of a police state, terrorism or fascism.

Collective Aesthetic Endeavors

Collective aesthetic endeavors were group artworks, usually murals or large quilt-like works, which relied on their size and collective facture—rather than the particular character of the individual contributions involved—to make their statement against the war. While this is the nature of the type, it was made obligatory by the characteristically low quality of individual contributions.

Advance Memorials

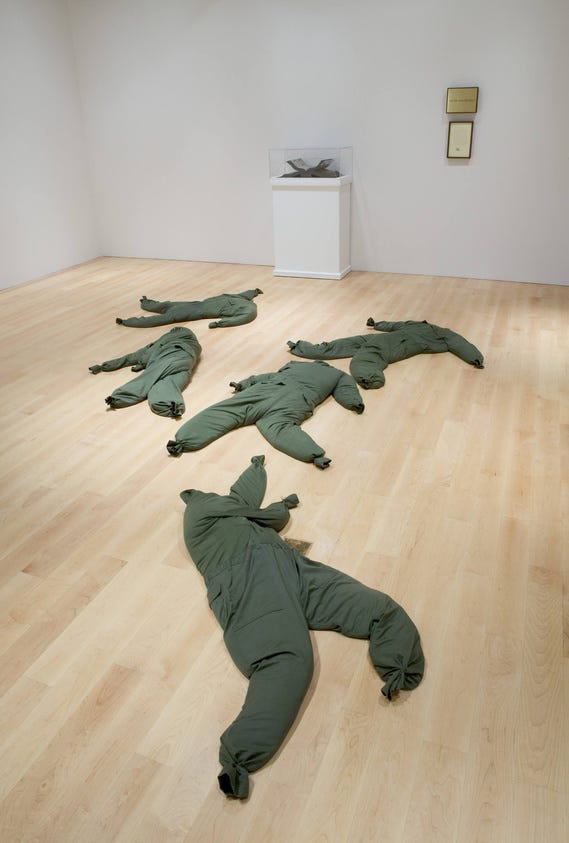

Advance memorials critiqued historical war memorials—the principle example in the United States being the national Marine Corps Memorial—through the following techniques: featuring dead soldiers or empty, grave-like spaces instead of valiant heroes; siting works on the floor without historical contextualization (as opposed to elevated, monumental podiums that clearly explained the historical event); and constructing monuments out of ephemeral materials.

Benefit Works

Benefit works were created by artists who wanted to donate their work to benefit the antiwar effort financially (in portfolios, auctions, and gallery exhibitions) but did not want to modify their work—which did not engage with the conflict—in any way to do so.

Again, hoping the above is helpful; please find ways to engage with the climate crisis; and see you in a few weeks.

Best,

Matthew