Death of an Artist, AI image tools, Kids, and Abstract Art: A Global History.

Art & Artists revamp...take one.

Welcome to the revamp of Art & Artists.

Thanks to some time provided by my recent layoff :), every two weeks I’ll highlight some of the best art content here.

As I explained last week, this content will span from writing to podcasts and will be sourced from a range of places, from art news websites but also scholarly journals. Thanks again for subscribing. Please share your comments and feedback so I can understand what to do more—and less—of.

I’ll begin with Death of an Artist. Chances are you’ve heard of this podcast about the tragic death of Ana Mendieta. Hosted by Helen Molesworth and produced by Pushkin Industries, it’s gotten a good deal of (good) press. I’d read about it since its September release but hadn’t taken the time to listen to it until last week. I told myself I knew the story. I questioned what else there was to say. I was also upset. Why did it have to take the subject of murder for an art podcast to get better investment and distribution? Yet I binged it. And it’s great. It’s one of the best art podcasts I've heard. (If you have other candidates, please share them below or message me. One I can think of is Last Seen, about the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum theft.)

Death of an Artist’s production value is high. The storytelling is strong. There are many story threads and there’s generous time spent unwinding them. Besides the story of Mendieta’s death, there’s a mini-history of feminism in the art world. There’s an extended discussion of the art world’s pervasive gender inequality. There’s a deeper reading of Mendieta’s work (outside of her death). There’s discussion of the tendency of the art world to separate the artist from the art. The podcast also covers the influence of museum exhibitions and acquisitions on long-term representation in our institutions.

Death of an Artist is also many voices, not only Helen Molesworth’s. There’s the late Peter Schjeldahl. There’s Amy Capellazzo. There’s the Guerilla Girls. There’s Julia Bryan-Wilson. And there are many others. Molesworth, in this way, is not just a talking head, like the lead in most art podcasts I’ve heard. She’s an inquisitive, relentless scholar-reporter. She steps back and gives voice to people behind the story like a skilled investigative journalist. Death of an Artist is also a personal story. It discusses Molesworth's effort to maintain respect for Andre’s work as she learns more details about Mendieta’s death and works at MOCA during Andre’s retrospective there. It also touches on her well-publicized firing from MOCA. (Only a bit though, because she signed an NDA.) So just try it. It’s a podcast but it’s deep and well-thought out and it sticks with you. I look forward to your thoughts.

AI image tools (e.g. Dall-E, Midjourney, Photoleap, Stable Diffusion, and others) have also been on my mind lately. I’ve played with some of them, primarily Dall-E and Photoleap, and I need to play with them more. I think art people, if they haven’t looked into these tools, need to understand them better though and pay attention to this fast-developing field. So I’m recommending one of the better articles I’ve read on the subject. It’s Kevin Kelly’s “Picture Limitless Creativity at Your Fingertips” in the current issue of Wired. Kelly says “Generative AI will alter how we design just about anything.” Is that enough to get you to read it?

After reading Kelly’s piece, I’ve started to form a sense of what may happen with these technologies. It seems they’re not going to replace fine art. (Though they could be an amazing brainstorming tool for fine artists.) What they will do is allow people—who lack the skills or the funds—to create illustrations for places where there are currently none. Think about the ability to insert an image as easily as you can type something out on your keyboard anywhere you want. Then think about how that could change emails, newsletters, websites, etc.

This doesn’t mean that the images will be great. Most of them will be very bad. But that’s generally the state of image production right now anyways. Especially online. Another thing I’ve learned about this technology is the importance of prompts—or the textual inputs that generate these images. It seems what will make images better is the skill someone has for creating textual descriptions of images because the root of these images in the first place is an AI creating connections between web-based captions and the images they refer to. This creation process could be a very long back-and-forth between man and machine to make a highly complex work of art. But, if you think about it, this is how one would use any tool to make any artwork, right? I also started to think, if the AI tools are generated through captions for images, the quality of art captions is so all over the place—and they could be so much better. It feels like yet another opportunity missed for art-making and art curation in the digital art space. Well, there is too much else to say here, so I’ll stop. Looking forward to your thoughts on this topic too.

I also want to recommend Lila Lee Morrison’s recent Artforum article “Living Memory.” Even if you didn’t see the movie Kids, or if it wasn’t a major event in your East Coast U.S. childhood (as it was in mine), this article is worth a read. Morrison was Chloë Sevigny’s roommate at the time Kids was being made. She discusses her small involvement in the film and with a new documentary “We Were Once Kids.” The documentary seeks to tell the story of the greater community Kids focused on. Generally, this is to show the inaccuracies of Kids and the (often traumatic) effect the film had on the real kids involved. Unfortunately, the documentary is having trouble getting distribution after being shown at multiple festivals.

In the Artforum piece, Morrison touches on some of the things Kids missed, and which are taken up in the documentary. It missed the central importance of skateboarding to the culture it focused on. It failed to foreground the experiences of non-male characters in the film. It failed to (after the fact) embrace the challenges those involved in the film had as the project made their lives into a world-famous image. It also blames Clark for misrepresenting teen culture through an adult’s eyes (versus its own). She also says Clark (through his own behavior) facilitated the addictions and destructive behaviors of the film’s young protagonists. I recommend this article to get a perspective on this important moment in U.S. culture. But I also can’t stop thinking that we are in a world of a million Kids movies right now, in a sense. Social media’s various curated accounts that capitalize on youth culture akin to the way Kids’ creators did probably will give birth to a legion of after-the-fact documentaries, showing all of the ways social media has traumatized and misrepresented our current youth culture.

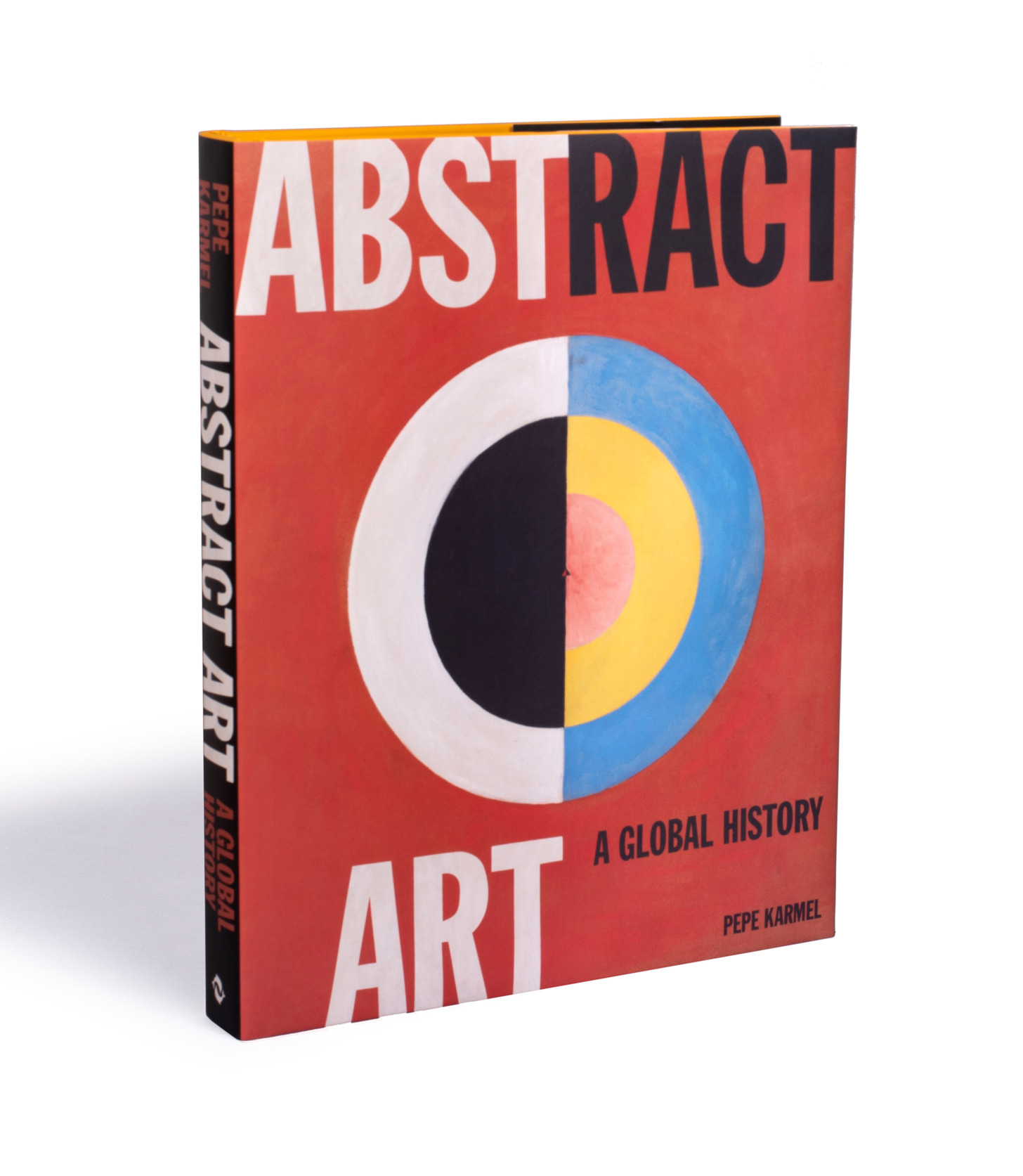

As a final note, I want to recommend two books. The first, which is quite academic, is the Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change, edited by T. J. Demos, Emily Eliza Scott, and Subhankar Banerjee. For anyone engaged with the issue of art and climate change, this seems like it should be a necessary volume, about to be released in (a more affordable) paperback. Its 450 pages feature fifty-five contributors from highly-diverse backgrounds who explore the range of issues surrounding climate-change-engaged art. There definitely hasn’t been a project this extensive focusing on art and climate change, which is arguably one of the—if not the—most important global issue of the present. The other book I want to recommend is Pepe Karmel’s Abstract Art: A Global History. A lot of great books published during the pandemic didn’t receive the exposure they should have. Karmel’s book is one of them. (And I’d like to think that my own book, A Year in the Art World, was one of them too.) Abstract Art is an ambitious re-organization of abstraction by a serious but accessible scholar of 20th-century abstraction. In contrast to the rhetoric of the purity of abstraction, espoused by earliest theorists, Karmel explains:

“The argument of this book, in brief, is that abstract artists always begin with a visual theme or archetype combining abstract forms with meanings generated by associations with the real world. The hidden images in the work of van Doesburg, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Malevich and af Klimt…are not idiosyncratic exceptions: they are the norm.”

Abstract Art is organized into five sections: Bodies, Landscapes, Cosmologies, Architectures, and Signs & Patterns with hundreds of examples. Having led a genome project to categorize all the world’s art, I deeply appreciate the significant effort that Karmel put into this book—to collect thousands of images and then divide them into discreet categories that actually hold up to interrogation. I also see the many possible ways this project could be so much more inclusive and ambitious through the use of the internet. Maybe that’s step two, Thames & Hudson :). Abstract Art is the rare combination of a beautiful coffee table and an amazing teaching tool that should not just sit on a coffee table. I hope anyone interested in abstract art—especially artists—will take some time with this volume. It deserves it.

That’s all for this week. Thanks again for subscribing and for sharing your feedback.

Love the list. Couldn’t agree more re the podcast. Wish there were more like it. I find it slightly discouraging that it takes a true crime element to make an art world story compelling enough for podcasters to put some effort and $ into it. Addressing some taboo and hush-hush aspects of the art world (gender and power-related) make it worth a listen regardless the subject.